This is Bella. To be clear, Bella is NOT an Unloved Pet. But she always looks a little sad and troubled in photos…

Word Business

Let’s start with language. It all starts and ends there. Doesn’t it? In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (Of all the gospels, John is the most stylistic and literary. He’s one of my favorites in the entire work of literature known as Bible. He was definitely on to something.)

And yet, this language thing never works the way you feel it should. This language thing. This put. The thing you want to put is a feeling. The thing you want to put is a mood. The thing you want to put is a blast: Of happy. Or sad. Of some sort of impossible (and implausible) awareness you believe you had or upon which you may be on the cusp. (I am always on the cusp of an awareness.)

This thing you want to put is a dream.

This thing you want to put doesn’t exist.

Music does it better, doesn’t it? “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” is a sentiment I’ve lifted before. It’s from Walter Pater. Specifically, from this essay, written in 1877.

Here’s the full paragraph:

All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music. For while in all other kinds of art it is possible to distinguish the matter from the form, and the understanding can always make this distinction, yet it is the constant effort of art to obliterate it. That the mere matter of a poem, for instance, its subject, namely, its given incidents or situation — that the mere matter of a picture, the actual circumstances of an event, the actual topography of a landscape — should be nothing without the form, the spirit, of the handling, that this form, this mode of handling, should become an end in itself, should penetrate every part of the matter: this is what all art constantly strives after, and achieves in different degrees.

To me, these notions of “form” and “matter” get muddied by things like Abstract Expressionism and ee cummings and things that happened with art and letters in the 20th century. Don’t they? I don’t know. I mean, you may disagree. But in 1877, a painting was mostly still a picture of something. In the 20th century, it began to change. A painting began to be more about paint on a canvas. That, in and of itself, became a “painting.”

And so: the matter started to become a little more like the form.

And so: painting as an art-form started to become a little more like music.

Confrontation/Avoidance

One thing I’ve been working on is a collection of flash non-fiction pieces. As is often the case, I’m working on this project to avoid working on two others. Mostly, I’m succeeding.

My greatest successes are also my greatest avoidances.

These flash non-fiction pieces are fun because each one is self-contained, like a poem or a painting. I can start and finish one in a relatively short period of time. And yet they all (hopefully) will contribute to a larger whole, possibly an illustrated book.

The pieces are little scenes of things I remember from when I was a kid. The spark for each of them isn’t language. The spark for each of them is a feeling or an image: A dead cat under a bush. A stick thrown at a friend. A game of rat-tail towel whips played around a pool in summer.

These little scenes mark the beginnings. They are the beginning things. They are the things I endeavor to put. And then, as is necessary when you engage in the word business, what comes out is letters and symbols and those things merely stand in for the put.

This is the nature of the thing.

This is the nature of writing. Of word business: Words and symbols that represent something else. The form can maybe lend itself to the matter. But the form and the matter are not the same. They are never the same.

It’s really a fucking terrible thing to do, this word business.

It’s really fucking terrible.

The Cheat

I recently watched a movie/documentary on the art of Ralph Steadman called For No Good Reason. In it, Johnny Depp, goes to visit Steadman in his home, and they discuss his art and they discuss Hunter S. Thompson and they discuss the time and culture and world those two weird, wonderful creatures lived in together.

It is a fantastic thing to watch.

What I mean to say, in case it is at all unclear (and it really shouldn’t be by the time you’ve finished with this post) is: I loved the film.

Steadman is full of great wisdom and words about art in general, his art in particular, and his and Hunter’s life and time. And as I watched it, I tapped furiously on my keyboard, transcribing some of the words he spoke as he spoke them. I’m not sure why. I’m not sure what good that will do. Why transcribe somebody else’s words. Somebody else’s symbols? So I can remember them? So I can put them on a t-shirt? So I can stab them into my goddamned arm?

The title of the film came out of the fact that Ralph would sometimes ask Hunter why they were doing a particular project and Hunter’s canned reply was: “For no good reason.”

It’s the why for everything, isn’t it? It has to be. Everything else will disappoint you.

Watch this clip of the movie put together by NOWNESS and you will get a feel for the thing:

This was a great part of the film, and it happens right at the beginning. I like how Steadman starts a thing with a splash of paint and how he refers to that as the “cheat.”

He says, “When I don’t know what to do, I do that. It’s kind of a cheat in a way because you don’t know if you did it because there’s nothing in your mind or if you did it because it might just lead somewhere.”

Then something emerges in the paint and he says, “I didn’t know what it was and then I suddenly thought I know what it is. It’s an unloved pet.”

And then he sums it up like this: “All I’ve done is made something that’s part of a frame of mind I might be in at the moment. What a terrible thing.”

What he calls a cheat could also be called “play,” and what I have always loved about music and art is that element of play and how it can blend with skill. The element of … well, maybe I’m not going to say anything, maybe this time there will only be nothing and more nothing. But wait, let me just do this, and this and, oh right, there it is: An Unloved Pet.

Maybe writing doesn’t have that same sort of play. Or maybe it does.

The “cheat” in my case (I suppose) is the dead cat under a bush. The cheat is the thrown stick hitting a friend’s face. The cheat is the game of rat-tail towel whips around the pool. The scene, the event. The set of smells and images. The emotions and the trembling and the raw. And all of that translated into words and put on a page or a screen.

And the thing that emerges somewhere between those words is: The Unloved Pet.

But it’s different, right? Writing? Words? I mean, isn’t it? Because the matter is so clearly different from the form. The matter of a dead cat is not even in the same ballpark as the words on the page. What is the “splash of paint” in writing? What is the “riff” in words and text? You can’t really start with an abstraction. Or rather, you can, but as soon as you begin to turn it into writing, as soon as you fill the symbols with the meaning which those symbols signify, you solidify it. You can’t blow a sound or splash some paint. You have to write a word. And as soon as you do that, you have left the feeling. As soon as you’ve done that, you’ve ruined the goddamned thing.

There is maybe no real abstraction in language. Maybe language is the running away from abstraction.

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.

The Big Bad Wolf

I’ve got this one piece about The Big Bad Wolf coming to my front door on Halloween. I was barely old enough to remember anything, though I have mental images of that house I lived in and that hallway and that front door. I’m not sure if what I remember about the Big Bad Wolf coming that evening (the set of images that I recreate in my memory about this particular event) are from the actual event or if they’re from the telling of the event to me by my family. Either way, they stir something, and so I’m not sure it even matters.

I’ve got this one piece about The Big Bad Wolf coming to my front door on Halloween. I was barely old enough to remember anything, though I have mental images of that house I lived in and that hallway and that front door. I’m not sure if what I remember about the Big Bad Wolf coming that evening (the set of images that I recreate in my memory about this particular event) are from the actual event or if they’re from the telling of the event to me by my family. Either way, they stir something, and so I’m not sure it even matters.

I’m not sure it matters because when I remember it, I recreate it, either way. I make the memory real by remembering it. I’m not just saying this. This statement is actually grounded in science: That the act of remembering is actually an act of creation. More than that, it’s an act of imagination.

So all you creative-non-fiction-has-to-be-absolute-fact-or-nothing blow-hards can suck it.

As of yet, I don’t know what the Big Bad Wolf piece (that’s what I’m calling it) is about yet, but I do know it’s not about the Big Bad Wolf. Or Halloween. In the end, those will just serve as vehicles to get to the Unloved Pet.

The Big Bad Wolf is my cheat.

The Big Bad Wolf is my splash of paint.

I’ll take whatever it gives me.

In the beginning was the Word…

Vowels and Consonants and Unbearable Moments

A few weeks ago, I found myself playing and re-playing the song “Heavy Bells” by J. Roddy Walston & The Business. It does a certain explosion to my brain. It does a certain big business up against my psyche. It makes my body move in a myriad of regretful ways. None of you should have to bear witness to any of this. None of you should absorb this in any direct, unfettered way. In this case, it is better that there is separation of form and matter. In this case, it is better for me to just describe it to you in words.

Anyway here is the video:

When I first played this song I did so without knowing the lyrics and it was good to do it that way. As abstract sounds, the vocals still conjure up for me certain visions which seem to fit with the music. To me, the lyrics, the way they sound, reinforce the mood of the song. This is a subjective thing. I realize that.

I mean, I like a 4/4 drum beat that’s a little bit on the bouncy, and does the doing like this here.

And I like a guitar that’s spare and breathes and picks.

I like a rock voice that can scream and break and be incomprehensible and still somehow hold itself together and sound like a feeling.

So I guess it’s all of that, really: The guitars and the beat and the particular quality of the voice. These things do it for me in this song.

And I understand other people will listen to this song and shrug and say “meh.” That’s the nature of music. It’s the nature of all art.

But humor me. And, if you can stand it, have a look at the lyrics:

I was ready to be disappointed when I read the lyrics. I was ready to be thrown out of the neat little abstraction this music had constructed in my head. But I wasn’t. The words are sort of their own abstraction. They are not so much words as part of the music. They don’t fully make sense. And I’m fucking glad they don’t. I mean, they sort of make sense. I mean, sure they do, right? They aren’t complete sound for sound’s sake, like some Cobain lyrics are (which I love, by the way… a mosquito, my libido). You can surely project sense on to these lyrics or infer sense from them, or whatever it is one does with sense and the making of it from words. But these words don’t make the kind of sense I had expected them to make. And their not-making-sense is the perfect amount of sense for them to make. They are good sounds to accompany this good music. They are a good set of vowels and consonants.

Most of the time, in writing, all I want to do is make good vowels and good consonants and have them form a rhythm and have that convey a mood.

Repetition. Chorus. Verse. Refrain. The format of music. The format of songs.

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.

Steve Almond, in his collection of essays and stories called “This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey,” says:

If you are now wondering why I write (I realize you’re not) the best answer I can give is that it’s the closest I’ve been able to come to song. I mean by this that my intent is always to reach some unbearable moment where time slows down and the sensual and psychological details compress and the language rises into what I call the lyric register. The rest is just chewing gum and string.

We are all just looking for unbearable moments.

Not Our Thoughts

I hear voices. I mean I don’t really hear voices. Not like that. Not like you’re thinking. Are you thinking that? I didn’t mean to suggest you were thinking anything. Look, I’m sorry.

But I do tend to listen to certain voices. Here’s what some of these voices say:

This thing here: It is a waste of time.

Or:

This other thing over here: It is a complete time suck.

Or:

There is no point to any of this. This is daydreaming. This is fuck all, motherfucker. You will die and then what? What will you have to say for yourself then? What will you have done?

Or:

You should have kids. That’ll give you some goddamned perspective. That’ll give you something practical and meaningful to do.

My friend says it’s good to separate the voices you hear from the reality or the “truth.” We are not our voices, he says. We are not our thoughts, he says. I love him and he is smart and yes I know what he’s saying and I kind of want to follow this line of … what? Thought? But at the same time, if we are not our thoughts, who or what are we? What else is there? What else is there other than our thoughts? A shell of skin filled with blood and bones? Is that enough?

What are we? Point to it. Describe it.

I think what he’s basically getting at is this: you can separate your thoughts from you and you can stand outside of them and look at them and say, “Those are my thoughts, and they are not necessarily correct.” And when you do that, you can gain some perspective and maybe you can even change your thoughts. Which is also to say: you can change the narrative. Which is also to say: you can change the words you use to describe your thoughts. Which is also to say: you can change.

You.

See the logic loop?

I’m being difficult, perhaps? Dense, maybe?

This might just be a simple case of me being limited in my brain matters. I’m pretty sure that’s all it is.

Proof

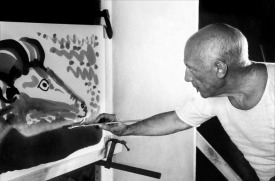

Back to the Steadman movie: Steadman cites Picasso as a big influence because of his “continuing persistent creative daily life.” According to Steadman, “Picasso proved it day after day after day. That something was on the page.”

Back to the Steadman movie: Steadman cites Picasso as a big influence because of his “continuing persistent creative daily life.” According to Steadman, “Picasso proved it day after day after day. That something was on the page.”

I love this.

I mean, is there anything else?

Is there anything else then waking up each day and creating your life? Finding new memories and recreating the ones you already had?

Is there anything else than proving, every single day, that something is on the page?

A Good Trip

Then there are these gems, loosely transcribed (by me) from the movie:

“Simply start a drawing and it will come out somehow on the other end. I won’t know how completely. But that makes it worthwhile.”

“If I knew what was going to happen before I started it, what would be the point?”

“If you surprise yourself still you really could have a good trip.”

We have lots of good trips as kids. We do.

All the stuff that gives me those kinds of trips now is the stuff I feel a little bad about doing. And I include art in that. And I include writing. I’ve said this before: The things that are going to kill me are the things that help me forget that I’m dying.

This is the punishment we inflict on ourselves as adults: to learn to stop doing the things that help us forget about death.

This is the way we become mature and enlightened.

This is how we, paradoxically, achieve a long life.

In her poem “Nostos,” Louise Glück writes: “We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.”

I still want to look at the world some more.

Authority Song

Issues with authority: I haz them. (surprise, surprise)

This maybe gets off-topic a little bit, but maybe not.

In any case, here’s another good quote from the film: “Authority is the mask of violence […] The desire to shock is also a way of getting back at authority.” – Steadman

One of the things people are so surprised about with Ralph Steadman is that he makes such angry, violent art and yet he is such a nice guy to speak to in person. He talks about this in the following RCN TV Interview. It gets to this idea of how art can be a weapon. It gets to this idea of how you can use art to get back at authority.

If you don’t want to (or can’t) watch the clip, he says, at about 7:40, the following

The only thing of value is the thing you cannot say. But you can draw it. You can’t say it in the same way as…you know, a drawing […] it could express it so much more vehemently, than if you had to find the correct paragraph to cover it, or chapter in fact, to say exacty what it was you wanted to say.

It’s that that makes it so powerful for me.

If I’m going to do anything, I may as well make it a weapon. I may as well make it to be what it wants to be.

I’ve searched for so many “correct paragraphs.”

I’ve tried so many different ways to say the thing I cannot say.

It’s a terrible thing, this word business.

Vertigo

One form of play, according to Roger Caillois is “vertigo.” It is the form of play concerned with “getting high.” It’s why kids spin around in circles until they fall down. It’s why we climb on top of our roof. It’s why we throw paint at a canvas. Or put a bunch of a words on a page. It’s why we take drugs. It’s maybe why we have sex. (Love is the usual excuse, isn’t it? To make us feel better about the whole thing. Love is the word we use instead of “brain chemicals” or “want” or “need” or “power” or “boredom.”)

And at the end of all of it, at the end of whatever thing we do or drug we take or roller coaster we ride, maybe we find something new. And maybe that’s all there is.

Or maybe we shock authority. Maybe we give a middle finger to whoever or whatever has fucked and raped us. To whoever or whatever keeps trying to fuck and rape us. And maybe that. Maybe that’s all there is.

Or maybe we simply surprise ourselves.

It’s possible I have not done anything worthwhile that wasn’t motivated by vertigo. And the interesting thing is it never seemed worthwhile at the time.

It just seemed like something I was doing instead of having a lie-down.

But then the thing happens.

The put.

The words. The symbols that represent the abstraction.

And sometimes the put turns out to be a favorite thing.

And sometimes the put is just an Unloved Pet.

But, even that: Even that can be a favorite thing. Even that can seem like music to somebody.

TAGS: Art | Chewing | HST | Hunter S Thompson | Music | Ralph Steadman | Writing

wow..i needed this soooo much … soooo much… i love it

thank you

xoxo

aww… thank you thank you thank you!